Processing¶

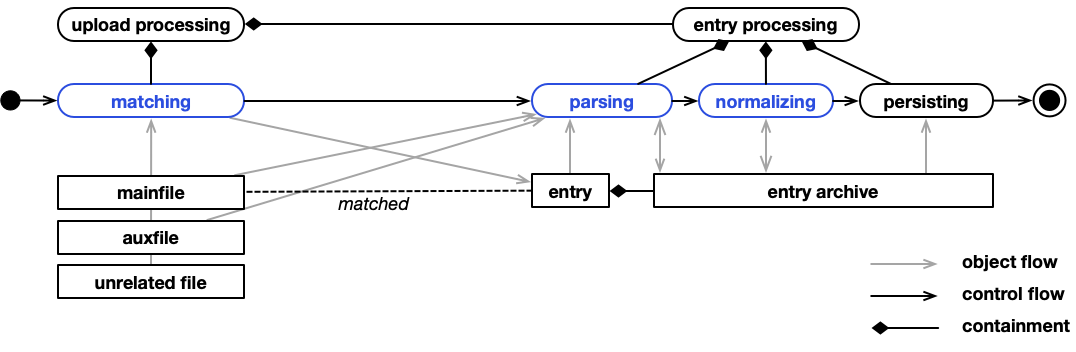

NOMAD extracts structured data from files via processing. Processing creates entries from files. It produces the schema-based structured data associated with each entry (i.e. the entry archives). To understand the role of processing in NOMAD also read the "From file to data" page.

Processing steps¶

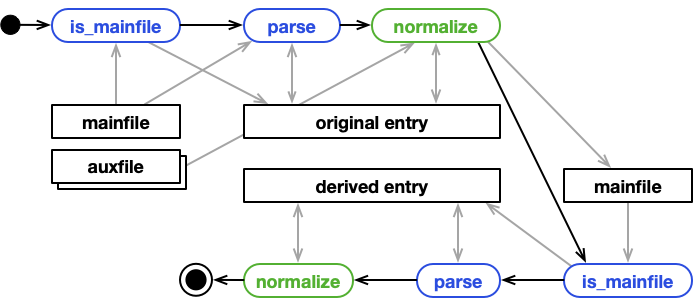

Processing comprises three steps.

- Matching files to parsers that can process them. This step also creates empty entries for matched files. Those matched files are now mainfiles and forever paired with the created entries.

- Parsing and normalizing to produce entry archives for matched mainfile/entry-pairs.

- Persisting (including indexing of) the extracted data.

Processing triggers, scheduling, execution¶

For most end-users, processing is fully automated and will be automatically run when files are added or changed. Here, processing is triggered by the file upload API. However, in more advanced scenarios, other triggers might apply. The three possible triggers are:

- New files are uploaded or existing files are changed. This includes creating and updating ELN entries. The respective file upload API will call the processing.

- The processing of an upload is manually triggered, e.g. to re-process data. This might be done via the UI, the API, or CLI.

- The processing of one entry, programmatically triggers the processing of other files, e.g. in a

normalizefunction.

Most processing is done asynchronously. Entities that need processing are scheduled in a queue. Depending on the trigger, this might happen in the NOMAD app (i.a. via API), from a shell on a NOMAD server (i.e. via CLI), or from another processing in the NOMAD worker. Tasks in the queue are picked up by the NOMAD worker. See also the architecture documentation. The worker can process many entities from the queue concurrently.

As an exception, entities can also be processed locally and synchronously. This means the processing is not done in the NOMAD worker, but where it is called. This is used for example, when an ELN is saved to have an immediate update on the respective entry with-in one API call.

Processed entities¶

We differentiate two types of entities that can be processed: uploads and entries. The same entity can only be scheduled for processing, if it is not already scheduled or processing. See also the documentation "from files to data" to understand the relationships between all NOMAD entities.

Uploads¶

Upload processing is scheduled if one or many files in the upload have changed. Upload processing includes the matching step, it creates new entries, and triggers the processing of new or afflicted entries. An upload is considered processing as long as any of its entries is still processing (or scheduled to be processed).

Entries¶

In most scenarios, entry processing is not triggered individually, but as part of an upload processing. Many entries of one upload might be processed at the same time. Some order can be enforced through processing levels. Levels are part of the parser metadata and entries paired to parsers with a higher level are processed after entries with a parser of lower level. See also how to write parsers.

Customize processing¶

NOMAD provides just the framework for processing. The actual work depends on plugins, parsers and schemas for specific file types. While NOMAD comes with a build-in set of plugins, you can build your own plugins to support new file types, ELNs, and workflows.

Schemas, parsers, plugins¶

The primary function of a parser is to systematically analyze and organize the incoming data, ensuring adherence to the established schema. The interaction between a parser and a schema plays a crucial role in ensuring data consistency to a predefined structure. It takes raw data inputs and utilizes the schema as a guide to interpret and organize the information correctly. By connecting the parser to the schema, users can establish a framework for the expected data structure. The modular nature of the parser and schema relationship allows for flexibility, as the parser can be designed to accommodate various schemas, making it adaptable to different data models or updates in research requirements. This process ensures that the resulting filled template meets the compliance standards dictated by the schema.

Processing is run on the NOMAD (Oasis) server as part of the NOMAD app or worker. In principle, executed processing code can access all files, all databases, the underlying host system, etc. Therefore, only audited processing code can be allowed to run. For this reason, only code that is part of the NOMAD installation can be used and no user uploaded Python code is allowed.

Therefore, the primary way to customize the processing and add more matching, parsing, and

normalizing, is adding plugins to a NOMAD (Oasis) installation. However,

NOMAD or NOMAD plugins can define base sections that use normalize functions that

act on certain data or annotations. Uploaded .yaml schemas that use a such base

section, might indirectly use custom processing functionality.

A parser plugin can define a new parser and therefore add to the matching, parsing, (and normalizing).

A schema plugin defines new sections that can contain normalize functions that add to the normalizing.

See also the how-tos on the development of parsers and schemas.

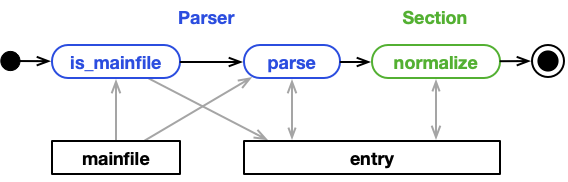

Matching¶

All parsers have a is_mainfile function. This is its signature:

If this function does not return False, the parser matches with the file and entries

are created. If the return is True, exactly one entry will be created. If the

result is an iterable of strings, the same entry is sill created, but now also additional

entries are created for each string. These strings are called entry keys and the additional

entries are child entries. See the also single file, multiple entries scenario.

In principle, the is_mainfile implementation can do whatever it wants: consider the filename, open the file,

reading it partially, reading it whole, etc. However, most NOMAD parsers extend a specialized parser

class called MatchingParser. These parsers share one implementation of is_mainfile that

uses certain criteria, for example:

- regular expressions on filenames

- regular expressions on mimetypes

- regular expressions on header content

See How to write a parser for more details.

The matching step of an upload's processing, will call this function for every file and on all parsers. There are some hidden optimizations and additional parameters, but logically every parser is tested against every file, until a parser is matched or not. The first matched parser will be used and the order of configured parser is important. If no parser can be matched, the file is not considered for processing and no entry is created.

Parsing¶

All parsers have a parse function. This is its signature:

This function is called when a mainfile has already been matched and the entry has already been created with an empty archive. The entry mainfile and archive are passed as parameters.

In the case of mainfile keys, an additional keyword argument is given:

child_archives: Dict[str, EntryArchive]. Additional child entries have been created for

each key, and this dictionary allows to populate the child archives.

Each EntryArchive has an m_context field. This context provides functions

to access the file system, open other files, open the archives of other entries,

create or update files, spawn the processing of created or updated files.

See also the create files, spawn entries scenario.

Normalizing¶

After parsing, entries are "normalized". We distinguish normalizers and normalize

functions.

Normalizers are Python classes. All normalizers

are called for all archives. What normalizers are called and in what order is

part of the NOMAD (Oasis) configuration. Normalizers have been developed to implement

code independent processing steps that have to be applied to all entries in processing

computational material science data. We are deprecating the use of normalizers and prefer

the use of normalize functions.

When you define a schema in Python, sections are defined as Python classes. These classes can have a function with the following signature:

These normalize functions can modify the given section instance self or the

entry archive as a whole. Through the archive, Normalize functions also have access to

the context and can do all kinds of file or processing operations from there.

See also processing scenarios.

Normalize functions are called in a particular order that follows a depth first

traversal of the archives containment tree. If section definition classes inherit

from each other, it is important to include respective super calls in the normalize

function implementation.

Processing scenarios¶

Single file, single entry¶

This is the "normal" case. A parser is matched to a mainfile. During processing,

only the mainfile is read to populate the EntryArchive with data.

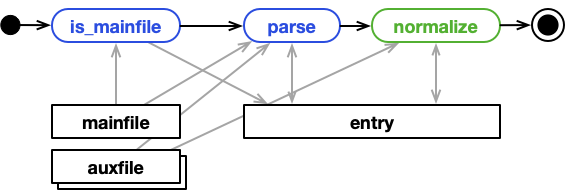

Multiple files, single entry¶

Same as above: a parser is matched to a mainfile. But, during processing,

the mainfile and other files are read to populate the EntryArchive with data. Only the

mainfile path is handed to the parser. Nothing, prevents it (or subsequent normalize functions)

to open and read other auxiliary files.

A notable special case are ELNs with normalize functions and references to files.

ELNs can be designed to link the ELN with uploaded files via FileEditQuantities (see

also How to define ELNs or ELN Annotations).

The underlying ELN's schema usually defines normalize functions that open the referenced

files for more data. Certain modes of the tabular parser, for example, use

this.

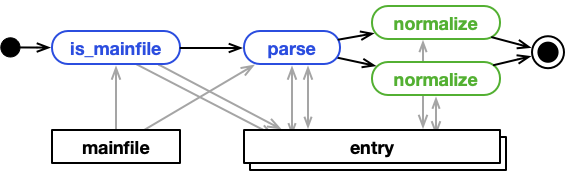

Single file, multiple entries¶

A parser can match a mainfile in two ways. It's is_mainfile function can simply return True,

meaning that the parser can parse this file. Or, it returns a list of keys. With the

list of keys NOMAD will create an additional child entry for each key, and the parser's parse function

is passed the archives of the additional child entries. One example is a parser for a tabular format that

produces individual entries for each row of the table.

Since normalize functions are defined as part of Sections in a schema and called for

section instances, the normalize functions are called individually for the entry and

all child entries.

Normally the IDs of entries are computed from the upload ID and the mainfile path. For entries created from a mainfile and a key, the key is also included in the ID. Also here the entry identity is internally locked to the mainfile (and the respective key).

Creating files, spawning entries¶

During processing, parsers or normalize functions can also create new (or update existing)

files. And the processing might also trigger processing of these freshly created (or updated)

files.

For examples an ELN might be used to link multiple files of proprietary type.

A normalize function can mix the data from those files with data from the ELN itself

to convert everything into a file with a more standardized format. In experimental

settings, this allows to merge proprietary instrument output and manual notes into a standardized

representation of a measurement. The goal is not to fill an archive with all data

directly, but have the created file parsed and create an entry with all data this way.

Another use-case is automation. The normalize function of on ELN schema might use

user input to create many more ELNs. This can be use-ful for parameter studies, where

one experiment has to be repeated many times in a consistent way.

Re-processing¶

Typically a new file is uploaded, an entry created, and processed. But, we also need

to re-processing entries because either the file was changed (e.g. an ELN was changed and saved

or a new version of a file was uploaded), or because the parser or schema (including normalize functions)

was changed. While the first case, usually triggers automated re-processing, the later

case required manual intervention.

Either the user manually re-processes an upload from the UI, because they know that they changed a respective schema for example, or the NOMAD (Oasis) admin re-processes (all) uploads, e.g. via the CLI, because they know the NOMAD version or some plugin has changed.

Depending on configuration, re-processing might only process existing entries, match for new entries, or remove entries that no longer match.

Strategies for re-usable processing code¶

Processing takes files as input and creates entries with structured data. It is about

transforming data from one representation into another. Sometime, different input

representations have to be transformed into the same output. Sometimes, the same

input representation has to be transformed to different outputs. Input and output

representation might evolve over time and processing has to be adopted. To avoid

combinatorial explosion and manage moving sources and targets, it might be wise to

modularize processing code more than just having is_mainfile, parse, and normalize

functions.

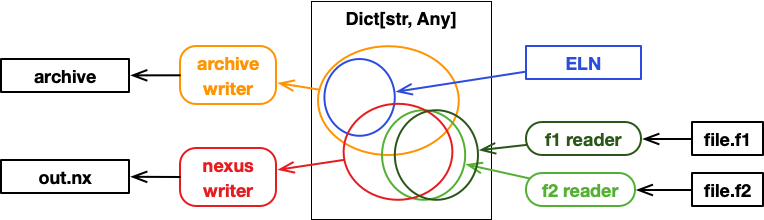

Readers: different input, similar output¶

Consider different file formats that capture similar data. Sometimes it is even the same container format (e.g. JSON or yaml), but slightly different keys, numbers are scaled differently, units are different, etc.

We could write multiple parser, but the part of the parser that populates the archive, would be very much the same, only the part that reads information from the files, would be different.

It might be good to define a reader like this:

and capture data in a flexible intermediate format.

Writers: metadata into archives, data into files¶

Two readers that produce a dictionary with the same keys and compatible values would allow to re-use the same writer that populates an archive, e.g.:

Similar to multiple readers, we might also use multiple writers. In certain scenarios, we need to write read data both into an archive, but also into an additional file. For example, if data is large, we can only keep metadata in archives, the actual data should be written to additional HFD5 or Nexus files.

Separation of readers and writers also allows to re-use parser components in a

normalize function. For example, if we consider the creating files, spawning entries scenario.

Evolution of data representations¶

If the input representation changes, only the readers have to change. If output representations change, only the writers have to be changed. If a new input is added, only a reader has to be developed. If a new output becomes necessary, only a new writer has to be developed.

Since we use a flexible intermediate representation such as a Dict[str, Any], it

is easy to add new keys, but it is also dangerous because no static or semantic checking

occurs. Readers and writers might be a good strategy to re-use parts of a parser,

but reader and writer implementations remain strongly connected and inter-dependent.

It is also important to note, that when using multiple readers and writers, the data items (i.e. keys) put into and read from the intermediate data structure might overlap, but are not necessarily the same sets of items. One reader might read more than another, the data put into an archive (metadata) might be different, from what is put into an HDF5 file (data).